Inductive reasoning is when we form beliefs about patterns or generalizations in the world after experiencing multiple occurrences. But do these beliefs provide us with knowledge that the same event will happen in the future? According to 18th-century philosopher David Hume, there is always a chance something unexpected can happen despite how certain we believe it will not. Hume called this the problem of induction.

Experiencing unexpected events does not necessarily deter us from thinking that there is uniformity or consistent patterns in the world around us. When the unexpected does happen, we revise our expectations to accommodate unlikely events into this view of uniformity because we are used to experiencing what is expected. Hume states that this is more of an inescapable habit of thinking than it is about uniformity in nature.

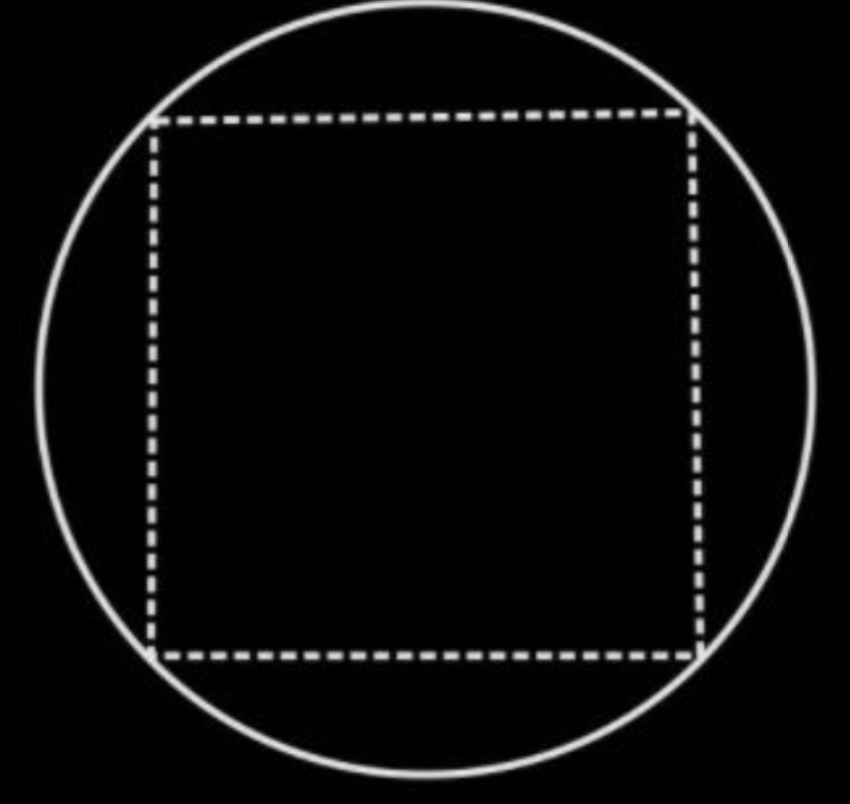

Another aspect of Hume’s argument is how we reason about matters of fact and relation of ideas. For relation of ideas, we are not able to imagine something out of the ordinary occurring. For example, we cannot imagine circles having four square sides or two halves, not making a whole. As such, relation of ideas are instances of knowledge.

For matters of fact, however, we believe the sun will rise tomorrow because this has always been the case, but we can imagine that it might not. We believe rain will fall to earth, but it is conceivable that it could fall upwards depending on one’s point of view.

Regardless of its apparent limitation on providing us knowledge, we are forced to use induction to make decisions everyday. When one pours milk on their corn flakes in the morning, one is justified in believing that they should eat their corn flakes quickly if they do not want to eat soggy corn flakes. The justification is that any time they have left corn flakes for more than 5 minutes with milk, they have turned soggy.

In the case of life and death experiences, like whether one should walk freely amongst caged and hungry tigers, a person is justified in choosing not to enter that cage even if they do not have knowledge of what will happen if they do.

Past experience or testimonial knowledge (matter of fact or inductive knowledge) from others tells us that this is a bad idea. Do not get in the cage with a lion. Prior experience tells us that although death is not certain, it is highly likely.

Induction is the best tool we have for decision-making, and that is why we rely on it. We are justified in using induction to predict what will occur in our lives because we are usually correct. But this does not mean we have knowledge of any future event.

References

Ladyman, J. (2001). Understanding Philosophy of Science (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203463680

Leave a reply to Inductive Reasoning – Phil Sci Edu Cancel reply